Historically, interest rates and the money supply have been matters of contention between agriculture and sectors like banking and manufacturing. More specifically, there is a longstanding opposition by farm groups of tight money policies like the gold standard, re: William Jennings Bryan’s critique. The reason is because when the supply of money is tight, it tends to cause higher interest rates and lower commodity prices, all other things being equal. During 2023 the U.S. money supply, as measured by “M2”, shrank dramatically due to Federal Reserve actions called “quantitative tightening” in addition to raising the cost of borrowing.

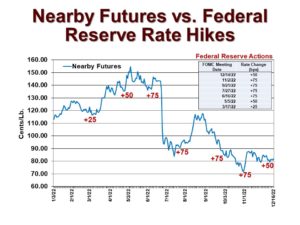

The reverse of this is also true, i.e., a rise in U.S. interest rates tends to increase the relative value of the dollar, which in turn could pressure the prices of dollar denominated commodities like cotton and crude oil. In terms of physical cotton, sharply rising interests rates would make it more expensive for farmers and merchandisers to borrow money, which implies a cost-push influence to cotton prices. The chart below definitely shows a positive correction between rising interest rates (the red basis point increases) and the longer term down trend of ICE cotton futures. Besides the above explanation, the decline in cotton prices is associated with weakening demand in the face of a slowing economy, the latter designed by the Federal Reserves interest rate hikes.

Beyond currency-interest rate interactions, there are at least two exogenous (i.e., non-currency) causes for interest rates to rise. First would be the recent actions by the Federal Reserve in raising short term interest rates. The latter has been in response to the inflation of 2022 (see graph below, and click here for more discussion). The second mechanism for rising interest rates is if U.S. borrowing credit ratings were downgraded, making the U.S. government a relatively greater risk to lenders. This situation is exemplified by the downgrade in U.S. bonds by Standard and Poor’s in August of 2011. More recently, Fitch downgraded U.S. debt in August of 2023. Just as if you or I were to suddenly get a bad credit score, there would be a more sudden, market-driven effect on the cost of borrowing — it would go up, in the form of higher interest paid by the U.S. government. Effectively, this could come about via the higher return demanded by purchases of U.S. treasury bonds. It hasn’t really happened in the U.S. since the August 5, 2011 downgrade, but it remains a possibility.